By Katharina von Plettenberg

The fashion industry faces a striking paradox. Consumers today are more aware than ever that their clothes are often made under poor and exploitative working conditions. However, many people still buy cheap fashion items as if nothing were wrong. In the last 15 years, global clothing production has nearly doubled, driven by fast fashion’s demand for rapid and low-cost output (Walk Free, 2023). It is the tension between awareness and ignorance that lies at the heart of fast fashion’s success.

Where do our clothes come from?

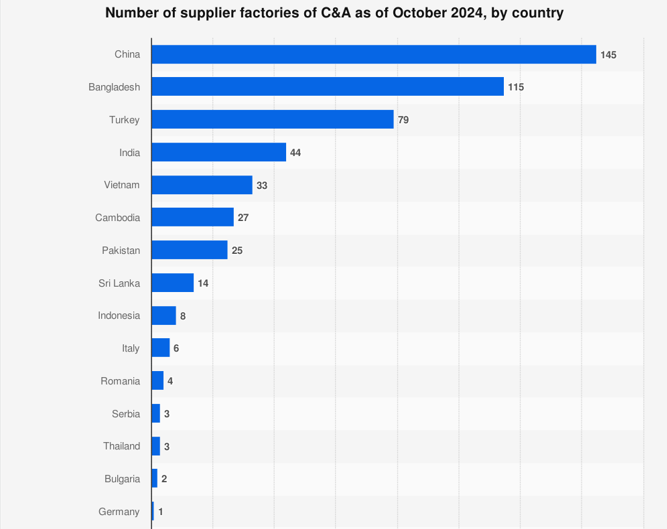

C&A is one example of a European fashion brand that outsources most of its production to low cost regions with weaker labour regulations. Although the company is headquartered in Europe, it relies heavily on production in Asia. China hosts the largest number of its supplier factories with 145, followed by 115 in Bangladesh, 79 in Turkey and 44 in India, while only one supplier factory is located in Germany. This is just one example of how less production takes places in Western Europe. Key factors behind this outsourcing are the lower employment costs and less stringent regulations in these regions compared to Western Europe, where less than one percent of the production occurs.

This global supply chain means that the true origin of cheap clothes is often a factory in Asia. It also means that social and legal protections for the workers are often very limited, resulting in an economic model whereby big brands in wealthy countries increase their profits by producing in low-wage countries and making labour rights difficult to monitor (Walk Free, 2024).

The Human Cost of Fast Fashion

More than 60 million people worldwide work in the textile and clothing industry, most of them in developing and emerging countries. The 2023 Global Slavery Index identifies garments as one of the products most at risk of being linked to forced labour. Bangladesh alone employs over 4 million garment workers, many of whom are women, who earn far below a living wage. Bangladesh’s newly raised minimum wage of 12,500 taka (approximately €94) covers only 38 % of what is needed to cover basic living standards (ILO, 2023). In addition to low pay, women in these factories are often denied fundamental rights such as maternity protection and access to adequate healthcare (BMZ, 2024).

Recently, investigative journalism and reports by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have focused on abuses in the world of work. In late 2022, an undercover documentary revealed shocking working conditions in Chinese factories producing clothing for the fashion retailer Shein. Workers were found to work 18-hour a day with only one day off per month and to earn just 0,035€ per item (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, 2024). This disclosure caused widespread public outrage. Shein acknowledged the labour violations at two sites and promised to improve conditions. However, recent undercover investigations by the BBC, suggest that conditions for workers have not yet improved. The EU Commission is also currently taking action against Shein for breaches of consumer protection in Chinese online trade (Tagesschau, 2025).

In response to these findings, political decision-makers are working towards greater accountability. In July 2024, the EU directive on corporate due diligence in the area of sustainability came into force (European Commission, 2024). The aim of this guideline is to encourage companies to behave sustainably, responsibly and entrepreneurially in their operations and global value chains. The new rules will ensure that companies recognize and address the negative impact of their actions on human rights and the environment, both within and outside Europe. Those that do not comply with the directive could face heavy financial penalties or legal action. In addition to legislative efforts at the European level, various national initiatives are being implemented to promote fair and more transparent supply chains. The national textile seal “Grüner Knopf” was launched by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development in September 2019. The initiative aims to protect people and the environment by certifying products that meet strict social and environmental standards and come from companies that take responsibility for their supply chains.

This is a good start, but what we still need more awareness of the processes and conditions behind the clothes we wear every day and keep buying often without asking where they really come from.

-

Ein starker Artikel, der unbequeme Wahrheiten offenlegt. Es ist erschreckend, wie bewusst wir über Missstände informiert sind – und trotzdem weiter Fast Fashion konsumieren.

Bibliography

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. (2024). China: BBC investigation reveals Shein suppliers’ workers face 75-hour work weeks & low wages. https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/china-bbc-investigation-reveals-shein-suppliers-workers-face-75-hour-work-weeks-low-wages-incl-co-comment/

Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung. Textilwirtschaft. https://www.bmz.de/de/themen/textilwirtschaft

C&A. (2024). Sustainability at C&A. https://www.c-and-a.com/eu/en/corporate/company/sustainability

European Commission. (2024). Corporate sustainability due diligence. https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/doing-business-eu/sustainability-due-diligence-responsible-business/corporate-sustainability-due-diligence_en

Tagesschau. (2025) Temu und Shein im Visier der EU: Wettbewerbsvorteil durch Umgehung von Regeln? https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/verbraucher/eu-china-temu-shein-100.html

Walk Free. (2023). Global Slavery Index 2023. Minderoo Foundation. https://www.walkfree.org/global-slavery-index/

Leave a Reply