By Katharina von Plettenberg

An increasing number of fashion brands are presenting themselves as sustainable, but often it’s just for show. To appear more responsible, companies like H&M highlight their “Close the Loop” initiative, while Shein promotes its supposedly eco-friendly line “evoluShein”. Greenwashing involves making environmentally friendly claims that sound good but aren’t supported by concrete action. In reality, the fashion industry continues to cause serious environmental and social damage.

Strategies of Greenwashing in the Fashion Industry

Fashion brands often mislead consumers with greenwashing tactics, such as using unclear buzzwords like “sustainable” or “eco-friendly.” They selectively highlight isolated eco-friendly efforts in their advertising while hiding the parts of their business that are far from sustainable(European Commission, 2023). Another strategy is to enhance products with eco-labels and certifications to increase credibility in the eyes of consumers, knowing that such markers signal higher quality and build trust. (Adamkiewicz et al., 2022). Brands also launch high-profile recycling initiatives, such as clothing take-back programs and the promotion of items made from recycled materials. However, these actions often create a misleading impression of a sustainable circular system, despite the fact that take-back schemes rarely result in actual clothing recycling. In reality, the promise of recycled fashion often ignores the fact that most garments are made from polyester, a material produced from fossil fuels that still serves as a cheap driver of growth and overproduction in the fashion industry (Greenpeace, 2023). Companies use these psychological mechanisms in a targeted way because they know when products are presented as sustainable, shoppers feel eco-conscious and may be willing to pay a higher price (Adamkiewicz et al., 2022). Such tactics are particularly common and used in the fast fashion industry, where the enormous production volumes make it almost impossible to achieve genuine sustainability.

The Consequences of Greenwashing

Greenwashing in the fashion industry misleads consumers by cultivating an image of strong environmental responsibility that does not reflect actual practices (Menno, 2023). Although many consumers are willing to pay more for products they believe to be sustainable, the growing number of misleading claims is making it increasingly difficult to trust brands promises. This growing skepticism is affecting both, the reputation of companies and consumers willingness to pay more for supposedly sustainable products (Menno, 2023). Beyond trust issues, the environmental damage remains.

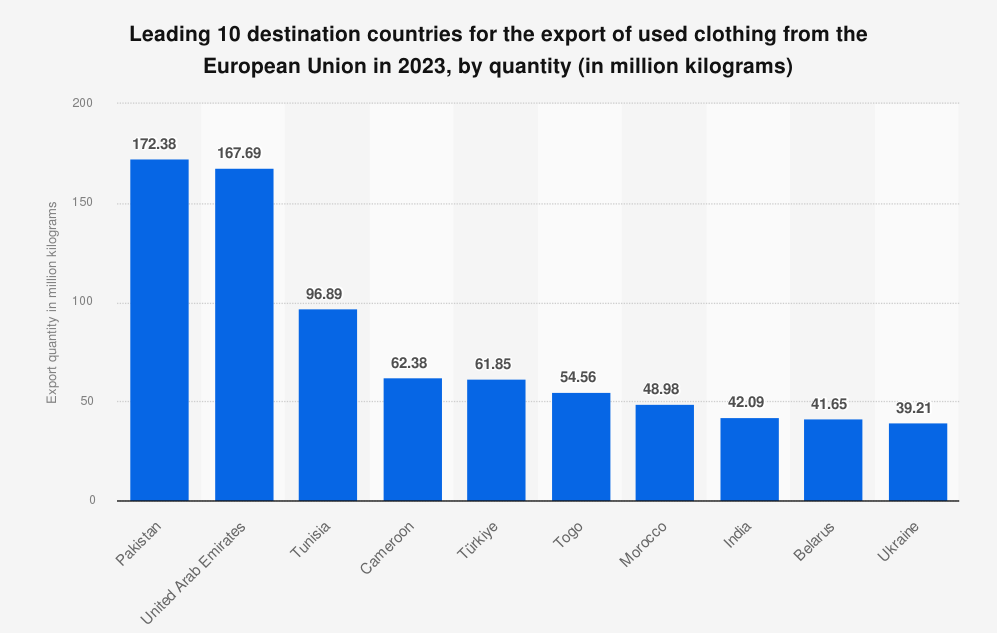

The dyeing and finishing processes in textile production are estimated to contribute to approximately 20% of global clean water pollution. In addition, a single wash of polyester clothing can release up to 700,000 microplastic fibers, which often enter the food chain (European Parliament, 2024). Each year, the world generates around 92 million tons of textile waste, which equals one truckload of discarded clothing every second. Only about one percent of this waste is actually recycled, the rest of textiles being either burned or sent to the dump (Leila et al., 2022). In 2023, the top three destination countries for used clothing exports from the European Union were Pakistan (172 million kg), the United Arab Emirates (168 million kg), and Tunisia (97 million kg) (UN Comtrade, 2024). These numbers highlight the alarming scale of fashion waste and about shifting the burden of disposal to countries in the Global South.

H&M’s Recycling Promise

The fashion giant H&M promoted its “Close the Loop” campaign by encouraging customers to return old clothes for recycling. The company claimed these garments would be turned into new ones, presenting the program as a step towards circular fashion. Reporters placed GPS trackers in donated H&M clothes in Sweden, but none of these remained in Sweden. Instead, they were traced to destinations as far as Hungary, India, Poland, Benin, and Kenya, often disappearing into the global secondhand waste stream (COSH!, 2024). The campaign was successful in creating a positive narrative, but the company did not disclose transparent data on actual recycling rates. This is a classic example of greenwashing, where the company creates an image of sustainability without actually delivering on it (Greenpeace, 2023).

How does politics respond to greenwashing?

In March 2023 the European Union proposed a directive on Green Claims, which oblige companies to substantiate environmental assertions with scientific evidence and have them independently verified (European Commission, 2023). For example, generic labels like “eco-friendly” or “green” could be prohibited unless backed by clear criteria and any claim such as “made with recycled material” must be quantified and explained to prevent consumers from being misled. This should not only protect consumers but also push brands toward more transparent and measurable actions. At the same time, consumer awareness needs to grow, encouraging people to look beyond green slogans and question what’s really behind them.

Do you look for sustainability labelling when buying your clothes and do you trust them?

Bibliography

Adamkiewicz, E., Becker-Olsen, K., & Potucek, S. (2022). Greenwashing and sustainable fashion industry. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 38, 100710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsc.2022.100710

COSH! (2024). Unravelling the illusion: H&M’s Close the Loop textile waste initiative – a greenwash? Retrieved from https://cosh.eco/de/artikel/unravelling-the-illusion-h-amp-ms-close-the-loop-textile-waste-initiative-a-greenwash

European Commission. (2023). Green claims initiative – Reliable information for consumers. Retrieved from https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/green-claims_en

European Parliament. (2024). The impact of textile production and waste on the environment (infographics). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20201208STO93327/the-impact-of-textile-production-and-waste-on-the-environment-infographics

Greenpeace. (2023). Greenwashing in der Fast-Fashion-Industrie: Wie H&M und Co. mit Nachhaltigkeit werben – und das Gegenteil tun. Retrieved from https://www.greenpeace.de/publikationen/Greenpeace_Report_Greenwashing_Fast_Fashion.pdf

Leila, N., de Jong, M., & Bouman, T. (2022). Consumer trust and sustainability claims: The role of greenwashing in the fashion industry. Sustainability, 14(5), 2628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052628

Menno, D. J. (2023). Consumer responses to greenwashing: The paradox of persuasive advertising. Journal of Business Ethics, 187(2), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04468-1

Leave a Reply