By Victor Schäfer

In the not-so-distant past, LGBTQ+ communities developed subtle fashion signals to communicate identity and desires. These codes arose out of necessity, when living openly was dangerous, clothing and accessories became a secret language. For example, the “hanky code” emerged in mid-20th century gay subculture: men tucked colored handkerchiefs in a back pocket to denote their sexual preferences (Feeld, 2023).

Other style cues were similarly coded. Wearing a single earring, especially in a specific ear, once subtly signaled that a man was gay. According to STITCH Magazine, this symbol became a quiet identifier in queer communities, especially during the late 20th century. In 1991, The New York Times even reported that gay men “often wore a single piece of jewelry in the right ear to indicate sexual preference” (Chun, 2021). The idea of a “gay ear” spread as an open secret, “left is right and right is wrong,” went the teasing rhyme, implying the right-side piercing marked homosexuality (Differio, 2024). And while such signals were never foolproof, they offered a form of recognition in hostile times. Queer women also developed their own visual codes: in the ’90s, wearing Doc Martens or clipping a carabiner to your belt loop could subtly indicate lesbian identity, until these styles became widely adopted and lost their original meaning (Manzella, 2023).

Over the past two decades, many of these once-clandestine style cues have leapt into the mainstream. What was once “too gay” for general society is now just fashion. Take the single earring: today it’s not unusual to see men of all sexual orientations wearing earrings (in one ear or both) purely as a style choice. The old “gay ear” code has faded so much that an earring no longer serves as a reliable orientation signal (Chun, 2021).

Perhaps the most visible example is men’s nail polish. Not long ago, a man with painted nails might raise eyebrows or be considered as making a bold queer statement. Now, it’s practically a pop culture norm. “Man-icures” have migrated from rock rebels like David Bowie and Prince to mainstream red carpets and TikTok feeds (Santos, 2021).

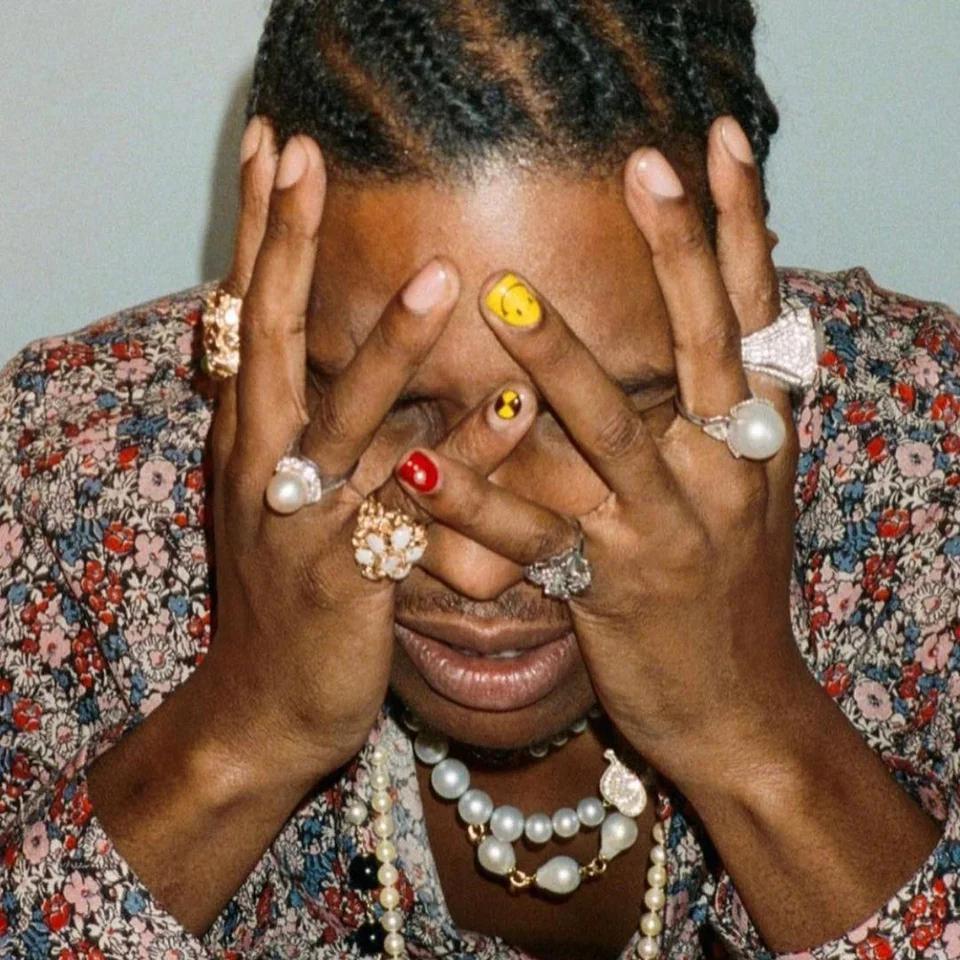

Scroll social media today and you’ll find straight-identifying male influencers and celebrities wearing colorful nail art simply because it looks cool. From A$AP Rocky’s artful manicures to former One Direction star Harry Styles painting his nails (and even launching his own nail polish line), polished nails on men have shed much of their stigma (Ramadhanu, 2022).

What was once a queer or punk-coded practice has fully entered everyday youth style. As one Vice article put it, the movement of nail art onto men’s hands went “from non-conformist stars like David Bowie to mainstream celebrity red carpet looks” in the blink of an eye (Santos, 2021).

Several forces have powered this transformation. High fashion designers and brands have actively blurred gendered fashion lines, making androgynous and gender-nonconforming looks chic. On runways in Paris, London, and New York, it’s now routine to see men in skirts or jewelry and women in traditionally masculine cuts. These sartorial crossovers, often pioneered by LGBTQ+ designers and tastemakers, trickle down to retail and streetwear.

Mainstream magazines and advertisers now often showcase queer-inspired aesthetics without necessarily mentioning their roots, because it simply reads as trendy or edgy to the general audience. Everyday culture has followed this trend – walk down a high street in Western Europe or the U.S. today, and you might spot a guy in a crop top or eyeliner, barely drawing a second glance. (Manzella, 2022).

The mainstreaming of queer-coded fashion is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it’s a huge win for visibility and acceptance. Styles that once marked one as an outsider can now be worn openly, by anyone, with far less fear. This normalizes diverse expressions of gender and breaks down rigid dress codes for everyone. Many LGBTQ+ folks feel a sense of validation seeing elements of their culture embraced widely, it indicates society has progressed, at least stylistically. Moreover, greater visibility can foster understanding, for example, a teenage boy in rural America might feel safer wearing nail polish to school today because he’s seen male pop stars do it and even straight classmates might think it’s cool. Indeed, when everyone is wearing a formerly queer-coded look, it destigmatizes that look. (Manzella, 2022; Santos, 2021; Ramadhanu, 2022)

On the other hand, there are real concerns about erasure and exploitation. When a coded style becomes just another mass-produced fashion trend, its original significance can fade away. The loss of specific queer signaling can make it harder for LGBTQ+ individuals to recognize each other in public, a classic case of cultural gaydar being scrambled. More painfully, the communities that created these styles often don’t get credit. Queer fashion innovators have long been copied by the mainstream without acknowledgment; as one lesbian culture critic noted, looks that lesbians were once shamed for are now Urban Outfitters staples, yet the originators rarely get the praise (Gutowitz, 2022). In the commercial rush, the deeper meaning of these fashion choices – born from resilience and rebellion – can be diluted into something “cute” or “edgy” for profit’s sake. In essence, when queer-coded fashion goes mainstream, there’s a risk of it being co-opted and stripped of context – the culture that birthed it sidelined in favor of a marketable trend. (Manzella, 2022; Santos, 2021; Ramadhanu, 2022)

Sources:

Feeld (2023). “The many histories of flagging.” https://feeld.co/magazine/playbook/histories/the-many-histories-of-flagging

Chun, A. (2021). “Queering the Earring: Piercings are Gay.” STITCH Magazine. https://www.stitchfashion.com/home//queering-the-earring-piercings-are-gay

Differio (2024). “Which Ear Is the Gay Ear? The Truth Might Surprise You.” https://www.differio.com/thedifferent/which-ear-is-the-gay-ear?srsltid=AfmBOoqYN4EEoskENp_NakSiZ74t-odWoLRu28QeCgbt_RWtHQMhiAY7#:~:text=,that%20a%20man%20was%20gay

Manzella, S. (2022). “What Does ‘Dressing Gay’ Even Mean Anymore?” Highsnobiety. https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/dressing-gay-meaning/

Santos, R. (2021). “Guys Are Wearing Nail Polish and We’re Here for It.” Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/men-nail-polish-art-trend-tiktok-gender/#:~:text=First%20came%20the%20baguette%20bags%2C,just%20women%20painting%20their%20nails

Ramadhanu, I. (2022). “The mainstreaming and commodifying of queer aesthetics.” TFR – The Finery Report. https://tfr.news/articles/2022/6/20/the-mainstreaming-and-commodifying-of-queer-aesthetics#:~:text=Therefore%2C%20it%20could%20be%20perceived,a%20trend%20owned%20by%20everyone

Gutowitz, J. (2022). „Sapphic Style Is Going Mainstream.“ Harper’s Bazaar. https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/a39357585/sapphic-style-is-going-mainstream/

Leave a Reply